w h a t . h o m e coming to BC's Sunshine Coast!

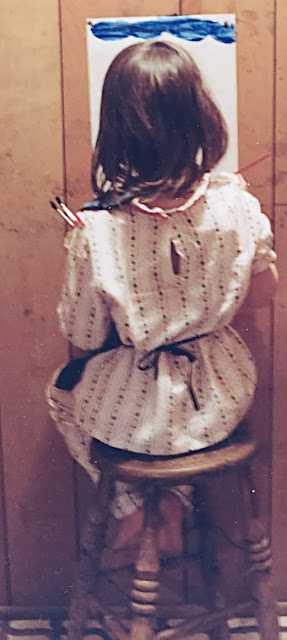

With huge thanks to the Gibsons Public Art Gallery and Canada Council for the Arts for putting their confidence in me, I can FINALLY announce that w h a t . h o m e will be coming home to BC, where it all began. In 2017 I began interviewing residents of BC's west coast on the subject of 'home'. I had some idea of where the topics might go, but I was surprised again and again by the amazingly heart-full, extremely unexpected, and often challenging stories that emerged. I've discovered through this work and other interview-based projects I've done that in any cross-section of humanity there will be a deep exploration of belonging, and a desire to make the best of always surprising circumstances. This project puts this on display. w h a t . h o m e installation in Amsterdam -- photo by Igor Sevcuk The woman in this image went from living as a small child in a mud hut in Mexico to living in a mansion. She now resides with her partner and children in British C...